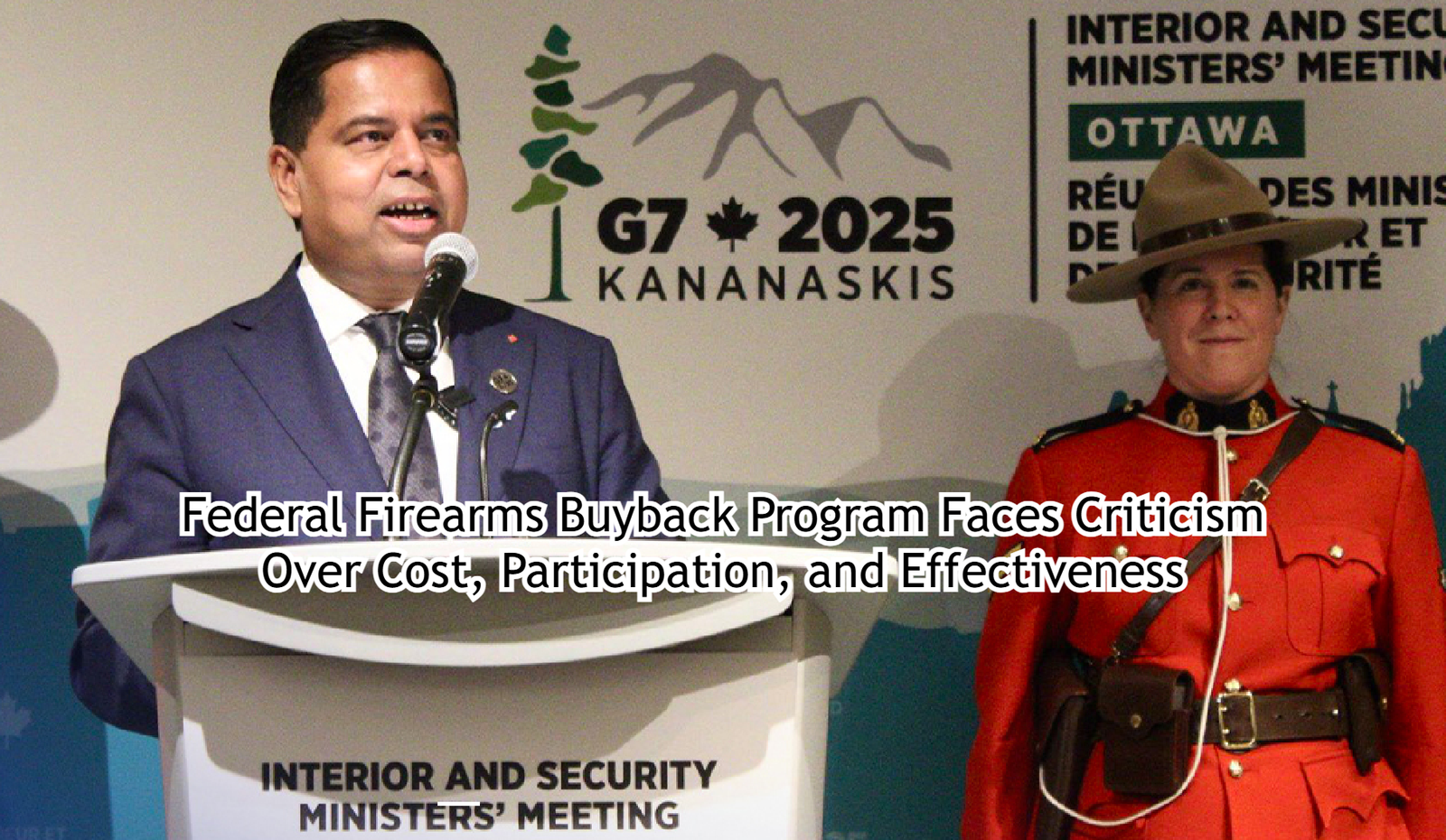

Canada’s federal firearms buyback program is drawing renewed scrutiny after a recent pilot phase saw very limited participation, prompting broader debate about its cost, implementation challenges, and overall impact on public safety.

The initiative was launched as part of the federal response to the 2020 prohibition on certain firearm models. It is designed to let owners of newly banned firearms voluntarily surrender them for compensation, with the aim of reducing the number of prohibited weapons in circulation.

Early results, however, have intensified criticism. Publicly discussed figures show that only a small number of firearms were turned in during the pilot, a level of participation that critics say falls far short of expectations. They argue the outcome underscores a gap between the program’s goals and the realities of lawful firearms ownership in Canada.

Licensed gun owners already operate under strict federal rules, including background checks, mandatory safety training, continuous eligibility monitoring, and secure storage requirements. Opponents of the buyback maintain that these individuals are not the primary contributors to gun crime, which they link more closely to smuggling and the illegal firearms trade.

Recent Statistics Canada analysis of homicides where origin information was available indicates that the vast majority of shooting homicides involve firearms that were not legally owned by the accused. In other words, the Canadian Government’s misguided focus on legal, licensed gun owners instead of criminals will not result in a significant reduction of gun violence.

Cost concerns have also become a focal point. The program has required extensive planning, staffing, and coordination with provinces, police services, and private contractors. With low participation in the pilot, critics question whether the significant public spending involved can be justified, particularly at a time of heightened attention to government expenditures and affordability pressures.

Implementation issues have added further complications. Several provinces have expressed reluctance to participate, citing jurisdictional disputes and doubts about the program’s effectiveness. Practical challenges — such as transporting, assessing, and disposing of surrendered firearms — have contributed to delays and rising administrative costs.

Supporters counter that firearms policy must be assessed over the long term and argue that reducing access to prohibited weapons remains an important public safety measure. Federal officials also emphasize that compensation programs are intended to respect property rights while enforcing updated regulations.

Even so, critics argue that resources would be better directed toward border enforcement, action against organized crime, and initiatives addressing the underlying causes of violence. They warn that focusing on compliant gun owners risks diverting attention from strategies that could more directly reduce criminal activity.

As the federal government weighs its next steps, the pilot’s results are expected to influence decisions about whether the buyback will be expanded, redesigned, or reconsidered. Future direction may hinge on participation rates, financial implications, and the program’s ability to demonstrate clear public safety benefits.

The discussion reflects a wider national debate over firearms policy — one that continues to balance public safety priorities, fiscal responsibility, and the rights of lawful gun owners across Canada.